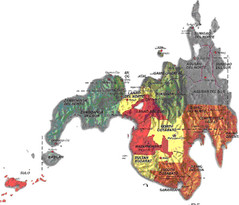

But the account at the Belmont Club is specially significant to yours truly, having been born and raised in the island of Mindanao, the second biggest island in an archipelago noted for its 7100 islands. And adding to the personal interest is the little issue of genealogy from my father’s ancestry. He owed his lineage to a rajah of Lanao (Samporna) whose time dated back to 1520s when Magellan first discovered the islands. In 1779, a Spanish friar named Pedro de Santa Barbara took the entire Samporna family, baptized it, and gave it a Christian name which we carry to this date.

Given these two significant details, our family has always been very eager and proactive to learn as much as we can about our origins, both in ethnicity and geography. Thus, most of the facts as detailed by the account at the Belmont Club have been common knowledge to most of us diligent enough to listen and/or do some of our own researches.

The following commentaries then are advanced either to supplement or clarify some of the issues brought out.

It is good to note right off the bat that one of Wretchard’s sources is a Jesuit, in the person of Fr. Javellana, who I gather is also from Mindanao. I say this because the Society of Jesus has been in the forefront of quality education in Mindanao, establishing 3 Ateneo schools many years ago. Two in the south, Zamboanga and Davao, and one in northern Mindanao, Cagayan de Oro, with the latter having been established way back in the 30’s.

When Wretchard calls it the Islamic insurgency, I surmise the intent is to tie it up with the current problems with radical Islamists under the umbrella of the GWOT. But for those growing up in Mindanao, the problem was simply the stubborn problems with the moros, a catch-all pejorative to denote those bandits who were not Christians, nor members of any of the many indigenous tribes scattered throughout the island but concentrated on the upland areas. As far as I know no religious tone was ever injected to the problem, not like the current upheavals. The violence and savagery may have been similar, but religion rarely got into the picture. To this day, the word Moro continues to be viewed with derision on both sides of the current conflict.

It was revealing to learn that the issue of slavery was a stiff determinant in the US resolve to deal with the Moslem problems in the south. This time slavery primitively practiced not by Rebs of the south, but by Moslems in their Morolands in the south.

Wretchard’s piece talks about basic infrastructures, such as roads and bridges, as enticements and offerings of noble intentions brought by the Americans to the island. And to this day we continue to see visible vestiges of those long-forgotten efforts. The No. 1 road distance marker, called kilometraje uno, is located in a place deep in Lanao called Camp Keithley, and from there it stretches throughout the entire island. As far as I know the main highway in Bukidnon continues to be called Sayre highway, obviously named for some past American.

On the issue of the cedula, which as related was quite a thorn on the side of the then-Moslem situation, beyond just noting that it was a carryover from the old Spanish regime, as I far as I know, it continues to be in effect in the current republic – still a thorn on the side, as expressed by many Filipinos. As a matter of fact, it comes in two versions. The cedula, which is called the residence certificate, is either A or B. Res. Cert. A is an annual fixed levy for, what else, being a resident of the country; and Res. Cert. B is based on a certain percentage of one’s income, both required before paying income taxes, and for most transactions with any government entity.

The case of the juramentados, or suicide attackers, as an apt juxtaposition of the current Islamist suicide bombers is an interesting analogy and I must admit the idea did not cross my mind until now. Again, growing up in Mindanao, one cannot be a stranger to the craziness and fatalism of the juramentados. Sordid tales abound on what we then considered a very unusual practice. That the subject, suffering from some irresolvable conflicts would induce himself into some kind of ghoulish trance, wrap a red bandana around his head, paint his face and body, arm himself with a long bolo (typically, a kris), go to any crowded place like a market place or your typical small town tabo, and start hacking strangers. And it stops only when the subject himself is killed.

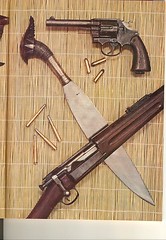

But this we learned was derived from an earlier practice widely used during the Moro wars against the US occupiers. Moro warriors armed with bolos, resolutely convinced that they were invincibly protected by their amulets, or anting-anting, would daringly charge head on to US entrenched positions, and would be met with a fusillade of rifle or pistol fire. And surreptiously validating the claim of invincibility, confused people related how these warriors amidst those formidable volleys would still be able to reach the US soldiers’ positions and use their bolos to inflict their damage.

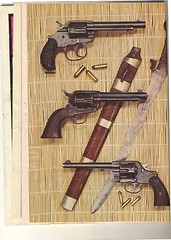

As it turned out the problem was not invincibility but was as mundane as “stopping power”. The typical US Constabulary officer was carrying a smallish .38 caliber revolver, with no sufficient power to stop an assailant dead on his tracks. Thus, Colt was commissioned to manufacture a higher caliber revolver to replace the standard issue. Thus was given birth the Colt .45 revolver, designed specifically to effectively stop a marauding moro warrior, or juramentado.

Some mementoes from that past taken from American Rifleman Magazine of January 1980: (The one on the right is the Colt .45, which replaced the earlier versions on the left.)

<

<UPDATE

A quote from Belmont Club:

In 1911, Pershing won that approval and announced a new law requiring Moros to surrender their firearms and forbidding them to carry edged weapons. Many Moros, for whom weapons were precious possessions, refused to give them up, and fighting broke out between them and the troops sent to enforce the order.

There is a lot more than meets the eye to the statement that Moros considered their weapons their precious possessions. Weapons continue to be regarded as both precious and prized possessions, and for many Moslem “warriors” more precious than their own families. They would rather be bereft of any material possessions or such abstractions as respect and honor, so long as they have their weapons to carry with them.

A family member used to recount his family company’s experiences logging in forest areas deep in Moroland. How these Moslems, most with no gainful employment, would approach their logging camps to ask for jobs. Except that there was only one type of job that they would accept – as security guards. And as further enticement, they commit to bring and carry their own weapons so the logging company does not have to issue them any.

As part of the appeasement process and since one is exploiting forest products in their own lands, companies had to hire them to survive and to operate in relative peace. But in turn, these companies had to hire their own security guards to watch over the Moslem guards. This rather odd arrangement had to work for them.

Extrapolate as much as you will what this almost innate love for and attached interest in weapons those Moros in Mindanao have and juxtapose that with what is similarly found in Afghanistan, Pakistan, and yes, Iraq. The trading of arms, amidst all the squalor and poverty, in those areas appears to always enjoy brisk business.

Quite unlike the Judeo-Christian axiom, from guns to plowshares.

happy new year! musta? zimm

ReplyDeleteSame to you, Zimm:

ReplyDeleteWe are experiencing very mild weather here, though the nights are really cold.

But I am looking forward to our coming trip to the lovely island.

Do you visit Cagayan de Oro?

Wish that somehow I could also trace our family's genealogywhich is much easier done in the States than here in the archipelago.

ReplyDeleteGlad that I'm able to post a comment once again here on your site.

Happy New Year!

Eric:

ReplyDeleteDid your problem with making comments start maybe when you upgraded to the newest version of Blogger?

My little genealogy project actually started when I was still in the Philippines. Now I have a hand-written graph (2'x4') that is now littered with names. Have resolved to make blueprint copies of it.

And I have expanded it to include my wife's and my late mother's, too.

Do try it. It is quite interesting and challenging.