The picture of a US soldier during wartime is one stark image evoking inspiration and the notion of valor from the beholder. Young and patriotic, maybe still naïve and not wise enough to the ways of the world, but already doing altruistic services for country and freedom. Americans are quite justified in heaping praise, gratitude, and care and concern for their safety and comfort away from hearth and home. Various celebrities through the USO visit them afield to try and bring some joyful and entertaining respite from the daily grind of soldiering in many theatres where wars and strife are aflame. Families try to bring cheers writing letters and sending packages containing items reminding the on-duty soldiers about home and loved ones.

The picture of a US soldier during wartime is one stark image evoking inspiration and the notion of valor from the beholder. Young and patriotic, maybe still naïve and not wise enough to the ways of the world, but already doing altruistic services for country and freedom. Americans are quite justified in heaping praise, gratitude, and care and concern for their safety and comfort away from hearth and home. Various celebrities through the USO visit them afield to try and bring some joyful and entertaining respite from the daily grind of soldiering in many theatres where wars and strife are aflame. Families try to bring cheers writing letters and sending packages containing items reminding the on-duty soldiers about home and loved ones.But by and large, while away from home, the lonely soldier has to make do and be self-sufficient in the inhospitable war-wracked areas that teams are assigned. Especially for those who spend days on end away from the little comforts that base camps and stations could provide; where some semblances of home can be found, such taken-for-granted amenities as home-cooked meals, radio music, some air-conditioning maybe, and basically a roof to rest weary heads and sleep under.

To the US Marine, he is taught early on from boot camp that his rifle is his best friend, there always by his side and reach to protect and shield him from the unimaginable perils of wartime conditions. And rightly so, he savors and respects that friendship like no other save maybe his fellow Marines.

But we know too well that even for the battle-hardened soldiers, fighting is not the only primal concern. He has to continue to live, to maintain his health, to renew his vigor and strength so he can fight another day. He has to sustain himself with food so he can continue to be an efficient fighting force in the pursuit of his high ideals.

And when a soldier is away from camp, away from the few amenities accorded him as a food-dependent human being, he has to rely on what he carries with him over and above the one best friend that will prolong his fighting life, his armaments.

And when a soldier is away from camp, away from the few amenities accorded him as a food-dependent human being, he has to rely on what he carries with him over and above the one best friend that will prolong his fighting life, his armaments. And that will be food. For on patrols, or sorties, or skirmishes away from camp or station, one does not notice any “chuck-wagon” tugging along the trip to provide hot nutritious and clean meals for the bone-weary hungry soldiers.

How does the individual soldier then in that situation continue to provide good and clean sustenance for himself? He can’t possibly go on fighting each day without regular food intake. We all know that as regular folks we normally require three square meals to get by doing our normal chores. How much more for the fighting soldier, under prolonged stress and fear and usually getting inadequate sleep.

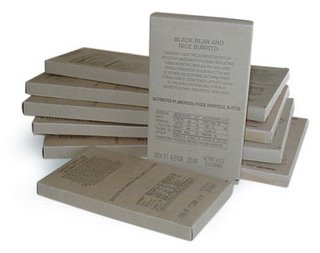

This is where the MRE comes in. It is the US Armed Forces’ packaged Meals Ready to Eat, wrapped in industrial-grade plastic and issued to individual Marines and soldiers. A 12”x8” dark brown or gray bulging packet containing all the necessary food items and condiments necessary to deliver a balanced meal. Three of these packages are supposed to account for three square meals a day, with required daily calories already accounted for.

This is where the MRE comes in. It is the US Armed Forces’ packaged Meals Ready to Eat, wrapped in industrial-grade plastic and issued to individual Marines and soldiers. A 12”x8” dark brown or gray bulging packet containing all the necessary food items and condiments necessary to deliver a balanced meal. Three of these packages are supposed to account for three square meals a day, with required daily calories already accounted for.Packed with his armaments and survival tools are these little packages weighing less than two pounds each. Heroic stories abound how soldiers would do away with toting the required number of these life-sustaining packages preferring instead to carry more armaments as part of their weight-laden gear.

Being the parent of three Marines, I am quite familiar with MREs brought home by the kids during furloughs or vacation.

Each package contains a complete meal, specifying a particular menu. And a very ethnically-diverse armed forces like the US have to provide for menus that will appeal to as many soldiers as possible.

Let us examine the exact contents of one such MRE.

Let us examine the exact contents of one such MRE.This particular meal is Menu No. 9 Beef Stew, and contains the following:

Main Entrée – Beef Stew, 8 oz - wrapped in thick foil and packed in a carton

Oat Meal Cookie, Chocolate Covered, 1.52 oz – wrapped in foil

Crackers, 1.41 oz – wrapped in foil

Plastic packet containing – iodized salt, tissue, creamer, Tabasco, 2 pcs chick lets, matchbook, sugar, iced tea drink mix, and moist wipe.

Cheese Spread With Jalapenos, 1.5 oz – wrapped in foil

Cocoa Beverage Powder, 1.5 oz – wrapped in foil

A Plastic Spoon

A Brochure showing nutrition values

One wrapper of Assorted Charms, 1 oz

And the ubiquitous MRE heater packet.

Here's a report on how these meals are prepared with the users preferences utmost in the minds of the food scientists:

A lot of cooks in the MRE kitchen

Men in lab coats and hair nets whet GIs' frontline appetite

Kim Severson, Chronicle Staff Writer

Monday, April 7, 2003

Natick, Mass. -- There is a seriousness of purpose here in the Department of Defense test kitchen these days.

In a sprawling, 1960s-style building set alongside a lake in this Boston suburb, two men in lab coats and hair nets bend over a stainless steel table covered in pale orange food bars each the size of a pack of cards.

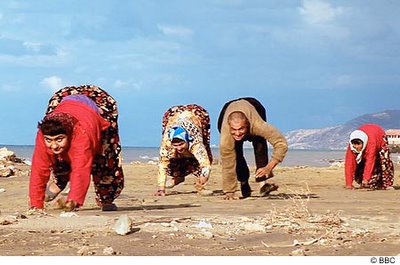

They're figuring out how to cram 2,100 calories into each bar, at the same time making sure the slightly sweet, grain-based rations will survive a drop from an airplane. The bars will be distributed as humanitarian aid, and might keep fleeing war refugees alive.

Over in the department where field rations are developed, there is a similar gravitas. Like anxious mothers, nutritionists wonder how the new Meals Ready to Eat (MREs) created for the troops in Iraq are going over. Are the soldiers eating?

In the U.S. Army Soldier Systems Center in Natick, where every recipe required to feed the 1.4 million people in the nation's armed services is developed, it's more than the standard worry a home cook has about a new dish. Military food scientists know that making sure a soldier is well-nourished is as important to winning a war as the right ammunition and a working gas mask. Food that doesn't taste good goes uneaten, compromising a soldier's health and performance. And the nutritionists know they also have to prevent battlefield anorexia, a condition where the stress of war dulls appetites to dangerous levels.

BIG CHANGE IN APPROACH

That's why the military's approach to feeding soldiers is radically different than it was a decade ago, with meals now tailored to the tastes of an ethnically diverse fast-food generation raised on tacos, teriyaki and Starbucks.

In 1991, when troops fighting the Gulf War tasted the first generation of the military's new field rations, the reaction was a fractured version of the don't ask, don't tell policy.

When the food scientists originally developed MREs, they didn't ask what the modern soldier might find appealing. But the soldiers told them -- and in no uncertain terms -- calling the field rations "Meals Rejected by Everyone." They tossed unopened brown plastic bags filled with casseroles and ham loaf into the desert, and had nicknames for the worst entrees, like the "four fingers of death." Translation: smoked frankfurters.

"We had kind of a father-knows-best mentality about the menus," said Gerald Darsch, joint project director for the Department of Defense's combat feeding program based here.

GIS' TASTES DRIVE THE MENU

Today, he says, everything is driven by soldiers' tastes. "Everything we create is war fighter-recommended, war fighter-tested and war fighter-approved, " he said.

Although soldiers are supposed to eat three MREs a day, they often don't. Soldiers on the move who find the MREs too difficult to prepare in the field or too bulky "field strip" their packs of food to make room for gear. And some units have reported having to cut back their rations to one meal a day as they wait for supplies to reach them. That makes what nutritionists put in each ration pack extremely important.

"We know food matters, especially on the front lines. What they eat has a very positive impact on mood, which has a positive impact on morale, which has a scientifically proven impact on performance," Darsch said.

Ever since the war in Iraq began, the MRE part of the program has been front and center. Each year, the military orders about 3 million of the 1 1/2- pound food packages from three commercial food manufacturers contracted to produce them. Since October, however, the order has doubled and the factories are on overtime. More than 48 million MREs are stockpiled in the warehouses of Kuwait.

VEGETARIAN OPTIONS

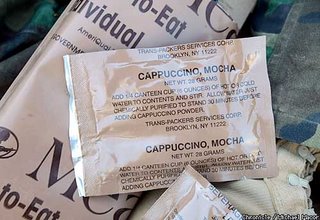

The new breed of MREs offers 24 entrees, including four vegetarian options like cheese tortellini and pasta Alfredo. The choices are geared to a more diverse fighting force that has a strong preference for spicier ethnic food. Some MREs feature Thai chicken, Jamaican pork chops or a gloppy cheese dish called Mexican macaroni. Little bottles of Tabasco or packets of cayenne or Mrs. Dash seasoning are included to pep up entrees.

Dried cappuccino and chai are replacing freeze-dried coffee. Powdered Gatorade-type drinks are being tucked into food packs for quick energy. The military has even developed its own power bar, called the HooAH! bar. And some rations contain dried versions of milk shakes in chocolate, strawberry or vanilla.

"You know when you shake this thing up and drink it down, it tastes like you're not here for 15 minutes," one Marine a few miles outside Baghdad told Chronicle reporter John Koopman.

YOUNG SOLDIERS GO FOR IT

Koopman, who ate the old C-rations as a Marine in the 1970s, reports that the new MREs are generally a hit with the young soldiers he's talked to. But, he said, they don't like the fancy stuff.

"What they like most of all is basically beef or meat. Being from San Francisco, I'm the only one who eats the vegetarian meals," he said. "The Marines love me because I'll take the pasta and vegetables."

However, any MRE that has a pack of Skittles or M&Ms is considered a good one, he said. Field studies have shown that young soldiers take comfort in name brands and commercial packaging, so some MREs feature morale-boosting snacks like M&Ms, Lorna Doone cookies, Skittles and Jolly Ranchers, which have become popular currency in poker games.

THE MILITARY'S REQUIREMENTS

The trick, of course, is making all of it work within the military's tight physical and nutritional requirements. The whole package can't weight more than a pound and a half, although the military brass would like them lighter -- and it can't be much larger than a hardback novel.

The food inside the tan plastic MRE bag must be edible for up to three years stored at 80 degrees. The packages have to be waterproof, vermin-proof and able to survive a 100-foot drop without a parachute.

Soldiers heat the food in the field. In the new version, cooking is done by an ingenious chemical heating sheet in a plastic pouch, which soldiers activate by simply pouring in an ounce of water.

Then there are the nutritional demands, as outlined in the eight-page Nutritional Standards for Operational Ratios (NSOR). That job falls to dietitian Judy Aylward at the Natick center. She has to ensure that each meal contains about 1,250 calories, with enough carbohydrate, fat, protein and vitamins to satisfy the surgeon general. That gives each soldier about 3,750 calories a day -- nearly twice the 2,000 calories most of us should eat to stay fit.

FAT 35% OF THE CALORIES

To cram so many calories in such a small space, Aylward has to be creative. Fat accounts for about 35 percent of the calories in each entree, five percent more than most nutritionists recommend. "There's just no way I can get the calories in the package without that fat content," she said.

Sugary drink mixes, jam and candy help pump up the carbohydrate and calorie count. To meet the micronutrient requirements, many of the grain-based items are fortified with vitamins. And because there are more women eating the meals than ever before, folic acid and iron are added.

In the vegetarian meals, getting enough protein and zinc is a problem, so Aylward makes sure those meals have packets of peanut butter. In fact, she is using so much peanut butter, soldiers are complaining.

"No one can eat that much peanut butter," wrote one soldier in a feedback form that hit Aylward's desk recently. "I suggest replacing it with more jalapeno cheese spread, which is excellent."

TWEAKING THE MENU

The crew at Natick constantly tinkers with the MRE menu. Behavioral scientists go through soldiers' trash during field exercises to see what is being thrown out, and study which items get traded or used in unexpected ways, like the cocoa powder and nondairy creamer that soldiers mix into crumbled crackers or pound cake to create "Ranger pudding."

Panels of soldiers and officers evaluate existing dishes and suggest which ones to eliminate. Next year, the Jamaican pork chop and the beef with mushrooms will be out, but New England clam chowder will be in. By 2005, the dreaded Country Captain chicken and Thai chicken will make way for a cheese omelet and chicken fajitas -- the latter a dish that couldn't be included until the commercial producers who contract with the military could wade through the specifications and find a way to keep flour tortillas fresh for three years.

"But they really want pizza and beer," Aylward said. "We're working on it -- the pizza, at least."